Bringing disabled women together, mobilising

and sharing through lived experiences

Kirsty Liddiard: Dis/Cinema: An Unshamed Claim To Beauty?

Reposted from Kirsty Liddiard’s blog with kind permission.

Last night I was lucky enough to be invited to introduce Sins Invalidâs film, An Unshamed Claim To Beauty? The film was screened as part of Dis/Cinema, University of Sheffield, which facilitates film screenings with themes of dis/ability, mental health, difference, and otherness. Check out its work here and follow Dis/Cinema on Twitter at @DisCinema. Below I share my introduction and slides. Not surprisingly the film instigated some powerful discussion which followed themes of privilege/power and race, class, gender and nation; the beauty industry and the economics of (bodily) shame; how we culturally come to be repulsed by otherness through fear; and our own experiences of being/enacting the spectacle of disability. A big thanks to Dis/Cinema and everyone who came along to contribute to such a stimulating night.

Introduction

When I got invited to facilitate this session, my immediate thought was, how on earth does one introduce Sins Invalid? What can I possibly say that can prepare you for the transgressive beauty that youâre about to witness in its Kickstarter-funded film, An Unshamed Claim To Beauty?

So I thought Iâd begin with a story of the first time I saw Sins Invalid. It was live, at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). I had just graduated my PhD, in which Iâd spent three years working with disabled people to tell sexual stories, and moved to Toronto in order to undertake my first postdoctoral position at the wonderful School of Disability Studies at Ryerson University.

This was a massive move for me, particularly culturally, as Iâm from Milton Keynes, which, as much as I love it, really is where culture goes to die*. Everything I saw that first week of living in a new country, far from home, was new, rich, and vivid. But seeing Sins Invalid, and sitting with its audience, opened me up to the possibilities of politicising pleasure, (or disabled peopleâs lack of intimate justice to pleasure, sexuality and love), through art for the first time; that art, politics and power enable silenced stories to be âloosed into the worldâ. These threads have persisted through my own research since that very night.

So what does it mean to âpoliticise pleasureâ, and why is it important to advocate for disability justice, the politic centred in the work of Sins Invalid? Activist Mia Mingus describes disability justice as a truly collaborative and intersectional movement that brings the body back in; as that which proudly centres accessibility; and which shatters the inherent Western, ableist and neo-colonial myth of independence. Patty Bearne, Co-Founder and Director of Sins Invalid, defines disability justice like this:

âA Disability Justice framework understands that all bodies are unique and essential; that all bodies have strengths and needs that must be met. We know that we are powerful not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them. We understand that all bodies are caught in these bindings of ability, race, gender, sexuality, class, nation state and imperialism, and that we cannot separate them. These are the positions from where we struggle. We are in a global system that is incompatible with life. There is no way stop a single gear in motion â we must dismantle this machine. Disability Justice holds a vision born out of collective struggle, drawing upon the legacies of cultural and spiritual resistance within a thousand underground paths, igniting small persistent fires of rebellion in everyday life. Disabled people of the global majority â black and brown people â share common ground confronting and subverting colonial powers in their struggle for life and justice. There has always been resistance to all forms of oppression, as we know through our bones that there have simultaneously been disabled people visioning a world where we flourish, that values and celebrates us in all our myriad beautyâ.

(Bearne, 2015)

http://sinsinvalid.org/blog/disability-justice-a-working-draft-by-patty-berne

For me, Sins Invalid offers us a new lens through which to come to know, see, and feel bodies in ways counter to the dominant culture. It makes space to think about bodies, self and desire in affirmative ways â that bodies with what disabled feminist Susan Wendell (1996:45) calls âhard physical realitiesâ â bodies that droop, sag, spit, dribble, spasm, ache and leak in ways deemed inappropriate (Liddiard and Slater, fc; Morris 1989; Leibowitz 2005) and minds that confuse, forget, hallucinate, or take longer to learn are not non-human or subhuman, but can open up new ontologies of pleasure and alternative economies of desire.

Disabled people have long had their intimate citizenship and justice deprioritised â dominant discourse renders our sexual lives, selves and bodies at best as unimportant, secondary to things like housing, care, education, and legislation; as if civil life is detached from intimate life; like the personal isnât political. We might think, in the current age of austerity, where in the UK and beyond, successive governments have served to denigrate disabled people, our communities and our families, that access to sexuality and intimacy is of lesser importance. That in a new world order controlled by Trump, May, LePenn and others, sexuality becomes, once again, the very least of our worries.

But austerity, neoliberal-ableism and global instability inevitably proffer new forms of precarity that drive us, at best, back into the normative body and self: meaning now is the time to politicise the impacts of such forces in our intimate lives; to claim, as the wonderful Tobin Seibers affirms, a sexual culture of our own.

Asserting, celebrating and living our own pleasures at this time in our history offers radical counter narratives. We can affirm the vibrancy of disability life through pleasure and desire in the face of social and literal death that austerity brings to our communities, and at the same time chip away at the normative boundaries of human pleasure which deem it unnecessary and grotesque for a range of marginalised bodies: disabled, fat, queer, Crip, black and POC, and genderqueer and Trans bodies. It is important, in times of such existential precariousness, that pleasure and sensuality (regardless of their form) are not relegated to luxury, but are means of survival and thus necessary for creativity, vitality and disability future.

I want to end with the words of the wonderful Eli Clare (2002: no pagination). Words which speak to the very bringing together of pleasure, politics and power that Sins Invalid demands: âI want to read about wheelchairs and limps, hands that bend at odd angles and bodies that negotiate unchosen pain, about orgasms that arenât necessarily about our genitals, about sex and pleasure stolen in nursing homes and back rooms where weâve been abandoned, about bodilyâand I mean to include the mind as part of the bodyâdifferences so plentiful they canât be counted, about fucking that embraces all those differences. Itâs time.â

Thank you: here is Sins Invalid. See the trailer and buy the film here.

* Sorry to those who live in/love MK â I do â but it ainât no Toronto for cultureâŠ

“Aesthetic Experience ” Allison Estergard (acrylic on canvas0. Showing this month at International Gallery of Art, Alaska, US (Photo courtesy IGCA)  Text – Sins Invalid: An Unashamed Claims to Beauty, Dr Kirsty Liddiard Research Fellow, The School of Education

Email: k.liddiard@sheffield.ac.uk Twitter: @kirstyliddiard1Â Â Â https//kirstyliddiard.wordpress.com

: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/

Disability Justice – A Disability Justice framework understands that all bodies are unique and essential, that all bodies have strengths and needs that must be met. We know that we are powerful not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them. We understand that all bodies are caught in these bindings of ability, race, gender, sexuality, class, nation state and imperialism, and that we cannot separate them. These are the positions from where we struggle. We are in a global system that is incompatible with life. There is no way stop a single gear in motion â we must dismantle this machine. Disability Justice holds a vision born out of collective struggle, drawing upon the legacies of cultural and spiritual resistance within a thousand underground paths, igniting small persistent fires of rebellion in everyday life. Disabled people of the global majority â black and brown people â share common ground confronting and subverting colonial powers in our struggle for life and justice. There has always been resistance to all forms of oppression, as we know through our bones that there have simultaneously been disabled people visioning a world where we flourish, that values and celebrates us in all our myriad beauty.” (Bearne 2015) http://sinsinvalid.org/blog/disability-justice-a-working-draft-by-patty-berne

‘I want to read about wheelchairs and limps. hands that bend at odd angles and bodies that negotiate unchosen pain, about orgasms that arent necessarily about our genitals, and sex and pleasure stolen in nursing homes and back rooms where we’ve been abandoned, about bodily – and I mean to include the mind as part of the body – differences so lentiful they cant be counted, about fucking that embraces all those differences. Its time.’ (clare, 2002:no pagination)

Discussion... In what ways did the film surprise you or touch you? what was your favourite part/scene in the film? Why? Was there anything about the film you didnt like or agree with? In what ways did the film make you think about disability, sexuality and/or activism in a different way to before? In what ways in current society are we made to feel shame about our bodies, disabled or not? How can we make (more) space for the arts, performance, activism, solidarity and justice in the Academy? In what ways might we enact disability justice – an appreciation that ‘all bodies are unique and essential and that all bodies have strengths and needs that must be met (Bearne 2015) – in the Academy/Higher Education?

—–

Blogs/websites from Sisters of Frida

Here we are featuring some of the blogs/websites by Sisters of Frida

Michelle Daley’s website

Hello! Iâm Michelle Daley and Iâm a proud black disabled woman. I was born and raised in the East End of London to Jamaican parents that moved to England in the 1950âs. I have worked in the disability field for over 15 years on international, national and local issues for public sector and voluntary organisations. I am privileged that through my work I am able to express myself and support others to do the same.

Hereâs where you can find out more about my career background.

Why follow me?

Through endless surfing it is clear that there is a lack of representation by British black disabled people in archives and on-line particularly from British black disabled women. I want to share resources including some of my own works, post blogs and for you to share your own experiences.

Kirsty Liddiard’s website

I am currently a Research Fellow in the School of Education at the University of Sheffield. Prior to this post, I became the inaugural Ethel Louise Armstrong Postdoctoral Fellow at the School of Disability Studies, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada.

Iâm a disabled feminist and public sociologist who believes in the power and politics of co-production and arts methodologies. To me, research is inherently political, personal, and embodied, and collaborative and always community-focused. This website details my scholarly and research interests, as well as my activist work. Please feel free to have a look around, and donât hesitate to get in touch if you have any questions.

Zara Todd’s adventure blog

I am a human rights activist from the UK. I have a background in disability, training and youth participation work. I identify as a disabled person and Feminist. I belive in equity and using intersectional and inclusive approaches.

This blog is primarily to document my Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Fellowship

A bit more about me

I am a born and bred Londoner who loves art, culture, travel and politics (although i am a left leaning non partisan).

I have a degree in psychology and a masters in Eastern European studies. I am interested in identity and decision making.

I have been involved in disability rights campaigning since childhood and have been active locally, nationally and internationally in the disabled peoples movement since the age of 17. Over the last 10 years I have worked in government and the NGO sector both in advisory and delivery roles.

Prior to this trip I was working for the biggest DPO in the UK Equal Lives .

I am a trustee of a childrenâs literature charity outside in world and a board member of ENIL and chair of itâs youth network.

I am also a director of Sisters of Frida, a disabled womenâs collective.

Eleanor Thoe Lisney’s website

Hi, I am Eleanor Thoe Lisney MA, MSIS, FRSA, AMBCS. I am passionate about access, human rights, disability culture, intersections of race, gender, disability. I am learning how to do digital strategy and smartphone film making. Recently I have become an emerging artist and making progress there.

I am a founding member and coordinator of Sisters of Frida, a disabled women’s collective and Culture Access.

Sophie Partridge’s website

I work as an actor, writer & workshop artist, if you are interested in employing me for any such work, I would love to hear from you.

I am a disabled Actor living in London, who trained with Graeae Theatre Co. I have worked extensively since, including my performance as Coral in the award winning Graeae play Peeling.

Other stage performance includes work with the David Glass Ensemble, TIE in Nottingham, Theatre Resource in Essex and Theatre Workshop, Edinburgh. My Media work also includes photo modelling, corporate video and radio.

I also Write and regularly contributor to various print & on-line publications, including Able Magazine (column writer for 2 years) and Disability Arts on-line (blog & reviews). This, along-side writing my solo piece, Song of Semmersuaq. Iâm also embarking on a new project.. so read this place!

Please read my resumés for more details of my work.

Lani Parker’s Sideway Times The Podcast

Sideways Times is a UK based podcast, in which we talk about the politics of disability and disability justice. Through this podcast I hope to have many conversations which broaden, deepen and challenge our understandings of how we work against ableism and how this connects to other struggles.

Kirsty Liddiard: Inaugural Sexuality Stream 2016 Call for Papers

This is a call for Papers for the Lancaster Disability Studies Conference 2016

The foundational text, The Sexual Politics of Disability, was âthe first book to look at the sexual politics of disability from a disability rights perspectiveâ (Shakespeare, Davies and Gillespie-Sells, 1996: 1). Ground-breaking in its contents and its approach, the sexual stories contained within the covers of the book â told by disabled people themselves â challenged the prevailing myth of asexuality and other tropes which render disabled people as perverse, hypersexual, or as lacking sexual agency.

Despite this scholarly activism, the sexual, intimate, gendered, and personal spaces of disabled peopleâs lives remain relatively under-researched and under-theorised in comparison to other spaces of their lives. Rarely are disabled people themselves authors or co-producers of this work. Where austerity policies dominate, we are unsure of how this impacts the possibilities for intimacy and relationships. Conversely, we lack evidence about the impact of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Significant gaps remain in our knowledge of disabled peopleâs experiences of sex, love and relationships, then, often in marked areas.

This inaugural sexuality stream marks the 20th anniversary of The Sexual Politics of Disability (1996). In this stream, we aim to celebrate and encourage the broad bodies of work that have emerged within the ever-expanding field of disability studies, gender studies and sexuality studies. For this stream, we will prioritise papers containing original social research, as a response to the relative dearth of empirical work within the field.

We are thrilled to have Don Kulick, Distinguished University Professor of Anthropology at Uppsala University, Sweden, as keynote speaker. His books include Travesti: sex, gender and culture among Brazilian transgendered prostitutes (1998), Fat: the anthropology of an obsession (2005, edited with Anne Meneley), Language and Sexuality (2003, with Deborah Cameron) and most recently Loneliness and its Opposite: sex, disability and the ethics of engagement (2015, with Jens Rydström).

We welcome papers on the following themes:

- Identity and imagery: masculinities, femininities, Queer and Trans* identities

- Intersections of gender, race, sexuality, class, nationality, age, and religion/faith/spirituality.

- Sex education and sexual health

- HIV/AIDS

- Pleasure, sensuality and desire

- Sexual and bodily esteem, confidence, self-worth and self-love

- Impairment, embodiment and corporeality

- Psycho-emotional disablism

- Barriers to sexual expression

- Youth

- Parenting

- Learning disability and sex/uality

- Mental health, distress and intimacy

- Intersections of personal assistance, residential and social care, and intimacy

- Sex work and sex industries

- Sexual, emotional and intimate-partner violence

- BDSM, kink, and fetish

- Online and cyber sexuality

- Sexual drugs, enhancements and technologies

- Human rights law and disabled sexualities

- Researching sex/uality: data collection, methodology and analysis

- Theoretical contributions: Critical Disability Studies, Feminist disability studies; Queer Theory; Crip Theory; Posthuman and DisHuman studies.

Contributions that reflect on any of these themes are invited from academic and non-academic researchers, scholars, activists, and artists. These themes are indicative only, and we will consider proposals that fall outside them so long as these relate to the overall conference stream. We welcome offers of traditional academic papers (20 minutes max) and also welcome proposals and presentations in alternative and/or creative formats (e.g. film, animation, poetry). Submissions should be made through easychair and please specify you wish to be considered for this stream.

If you have any other questions, donât hesitate to get in touch with Kirsty:Â k.liddiard@sheffield.ac.uk.

Please see here for the Mad Studies stream and here for the main conference call for papers.

Kirsty Liddiard is on Sisters of Frida’s Steering Group. She is currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate within the Centre for the Study of Childhood and Youth, at the University of Sheffield, working on a transdisciplinary research project entitled Transforming Disability, Culture and Childhood: Local, Global and Transdisciplinary Responses. Prior to this post, she was the inaugural Ethel Louise Armstrong Postdoctoral Fellow at the School of Disability Studies, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada.

Kirsty Liddiard is on Sisters of Frida’s Steering Group. She is currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate within the Centre for the Study of Childhood and Youth, at the University of Sheffield, working on a transdisciplinary research project entitled Transforming Disability, Culture and Childhood: Local, Global and Transdisciplinary Responses. Prior to this post, she was the inaugural Ethel Louise Armstrong Postdoctoral Fellow at the School of Disability Studies, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada.

Sisters of Frida Team

Eleanor Lisney is a campaigner, founder member, public speaker and director of Sisters of Frida. She is an access advisor, an aspiring creative practitioner and co founder of Culture Access CIC, which is about supporting access, bringing an inclusive edge intersectionally. Recently, Eleanor joined the TSIC Advisory Board and was working on a project with them for the London Funders. She was also on the Disability Arts Online Board. Presently she is on the Board of Directors of EVR ( End Violence and Racism Against ESEA Communities) and on the Liberty (Festival) Advisory Group.

She was born in Malaysia and has lived in Strasbourg, France and studied at Austin, Texas. She has two grown up children and a grandson. https://linktr.ee/eleanorlisney

…..

Tumu Johnson is a mental health worker and group facilitator with experience of working in front line support services, research and community organising. She is currently studying for a Masters in Mental Health Studies whilst working in the NHS and also provides freelance training around mental health and wellbeing.

Tumu is committed to making the world a more accessible place and fighting for the rights of disabled people. She is a feminist who takes an intersectional approach and hopes to draw on her experiences as a black disabled woman to contribute to achieving social justice.

Rachel O’Brien is Community Organiser (Coordinators and Networks) at Amnesty International UK. Previously, she was the Independent Living Campaigns Officer at Inclusion London after working at the National Union of Students as the Disabled Studentsâ Officer where she did work on movement building and political education, and campaigns around stopping the privatisation of the NHS and stopping and scrapping Universal Credit.

Advisers

Sarah Rennie is a former solicitor. Her day to day work is research and governance advice. However, Sarah delivers Disability Equality Training nationwide and acts as a consultant for select clients on internal equality working groups.

She was a steering committee member of Sisters of Frida, a co director and has now taken on an advisory role to the organisation.

Kirsty Liddiard Kirsty Liddiard is a feminist disability studies scholar and disabled researcher whose co-produced research centres on lived experience, emotion and embodiment as core axes through which to understand the everyday lives of disabled people and their families. She is currently a Senior Research Fellow in the School of Education and iHuman at the University of Sheffield. She is the author of The Intimate Lives of Disabled People (2018, Routledge) and the co-editor of The Palgrave Handbook of Disabled Childrenâs Childhood Studies (2018, Palgrave). She is also co-editor of Being Human in Covid-19 (2022, Bristol University Press) and a co-author of Living Life to the Fullest: Youth, Disability and Voice (2022, Emerald). Her current project, Cripping Breath: Towards a new cultural politics of respiration, funded by a Wellcome Discovery Award, explores the lives of people who have had their lives saved or sustained by ventilatory medical technologies.

…

Lani Parker (she/her) is a facilitator, trainer, consultant and coach with a background in providing advice, information and advocacy within disabled peopleâs organisations. She has also been involved with migrant solidarity and abolitionist movements. From 2015 to 2022, she was a steering committee member of Sisters of Frida, a co director and has now taken on an advisory role to the organisation. Examples of her work can be found at https://sidewaystimesblog.wordpress.com and www.bolderlives.co.uk. She is passionate about making connections and developing new ideas and visions that centre disabled people and other marginalised groups.

Engaged Allies: Academia, Activism & Crip Feminist Power

Reblogged from Kirsty Liddiard who helped in organising this event – with thanks also to Armineh Soorenian (Sisters of Frida North)

Screening AccSex: Disabled Women Activism & Sexuality event, University of Leeds, 2015

Screening AccSex: Disabled Women Activism & Sexuality event, University of Leeds, 2015

The above photograph represents the end of a brilliant day-long event which I helped co-organise along with some lovely folk from the Centre for Disability Studies at Leeds University and the disabled womenâs cooperative, Sisters of Frida (of which Iâm a proud member). The day was action-packed: a talk from Sarah Woodin (Leeds University) on disabled women and forms of violence; a presentation on youth, feminism and the cripping of the political/personal dichotomy by Icelandic activists Freyja HaraldsdĂłttir and Embla ĂgĂșstsdĂłttir and their organisation, Tabu; a UK premiere of Accsex (2014), a film which uncovers the pleasures (and precarities) of the connections between disability, sex/uality, gender, and race; and a Q&A with its creator, film-maker Schweta Ghosh. You can watch the trailer for Accsex (2014) here.

Within stifling dichotomies of normal and abnormal, lie millions of women, negotiating their identities. Accsex explores notions of beauty, the âideal bodyâ and sexuality through four storytellers; four women who happen to be persons with disability. Through the lives of Natasha, Sonali, Kanti and Abha, this film brings to fore questions of acceptance, confidence and resistance to the normative. As it turns out, these questions are not too removed from everyday realities of several others, deemed âimperfectâ and âmonstrousâ for not fitting in. Accsex traces the journey of the storytellers as they reclaim agency and the right to unapologetic confidence, sexual expression and happiness.

â Ghosh (2014)

A powerful line up makes for a powerful event, in more ways than one. To look again at the photograph, itâs far more than just a shot in time. It represents more than students, lecturers, activists, community members, allies, or otherwise interested people seeking alternative understandings of disability and gender coming together to connect (as if that isnât exceptional enough). To me, the photograph is emblematic of the exciting possibilities that can emerge when the best parts of academia and activism come together. In this short post, Iâd like to very briefly sketch out some points as to what this means to me as a disabled woman and scholar:

Safe(r) Spaces: Firstly, academic/activist events like this show that we can create (and demand) safe(r) spaces to speak about our lives as activists, campaigners, scholars and women.  Events like this offer rare occasions for disabled women and their allies to come together, think together, politicise and rage together, and take solace in sharing intimate knowledges of our lives (that are seldom acknowledged or celebrated anywhere) together.

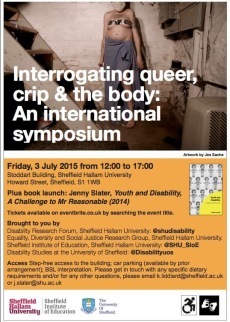

Resistance and intellectual freedom: In the context of the Academy, the fusion of academia and activism can offer refreshing spaces of resistance, creativity and (intellectual) freedom. Never has this been more important to counter the significant corporatisation and marketisation of higher education in the neoliberal University, and what some have called the privatisation of knowledge. Another recent event I helped organise, Theorising Dis/Ability, worked in similar ways. You can access the talks from the Theorising Dis/Ability seminar here. Iâm currently co-organising another event with my friend Jenny Slater (Sheffield Hallam) around the intersections of queer and disability/crip activism, Interrogating queer, crip and the body: an international symposium, for which you can access free tickets here.

Interrogating queer,crip & the body: An international symposium

Interrogating queer,crip & the body: An international symposium

Making space for activist scholarship: For me personally/politically/professionally, academic/activist collaborations enable me to continue the work I love to do. It is a reminder of the importance of activist scholarship, which needs such spaces to not just survive, but thrive. Iâm lucky that these loves are nurtured by many, many brilliant colleagues. For example, see the âdishumanâ manifesto that Iâm working on with exceptional folk like Katherine Runswick-Cole (MMU), Dan Goodley (University of Sheffield) and Rebecca Lawthom (MMU). This work is as theoretically rich as it is grounded in disabled peopleâs lives and meaningful social and political change.

The politics of visibility and disruption: Most importantly, academic/activist presences like those within the event above solicit/invite/welcome a multitude of bodies, minds, selves, knowledges and politics into the Academy. These are often bodies and selves that are at best tolerated, and at worst violated, in neoliberal educational spaces. To be present in the Academy in such ways â to proudly take up space, make noise, and be disruptive within the the very walls that so often exclude us â affirms Crip feminist power. Crucially, it does so in an academic landscape where we are largely absent as students, let alone as educators, speakers, creators, and leaders.

Tabu: the political is personal

Note: This post is dedicated to the memory of Judith Snow who passed away on 31st May 2015. A proud disabled woman, visionary and advocate, she truly changed the world.

Storying Disabled Women’s Sexual and Intimacy

This article by Kirsty Liddiard was first published on the Shameless Mag.Â

Kirsty will be coming back back to the UK summer 2015 – we look forward to hearing more from her.

In the dis/ableist cultures in which we live, disabled peopleâs(1) sexual selves are seldom acknowledged. We are, almost routinely, ascribed an asexual identity(2), where we are assumed to lack any sense of sexual feeling and desire. We are also deemed sexually inadequate because of the ways in which our distinctive sexual pleasures and practices, and Othered bodies and minds, contradict deep-seated sexual norms. Rather confusingly, some disabled people, typically those with the label of cognitive impairment, are considered to have sexualities that they canât understand â a âhypersexualityâ that they canât control; and sexual desires that are somehow âdeviantâ or dangerous to others. Further, where we are avowed a sexual identity, it is usually only within the realms of heterosexuality, leaving LGBTQQI2-S(3) disabled people further marginalized.

Within this, the sexual and intimate lives, selves and bodies of disabled women are further marked by patriarchy, sexism and misogyny (the hatred or dislike of women or girls). For clarity, I use the term patriarchy to refer the social hierarchy through which (cisgendered) males hold the greatest privileges in terms of social and sexual power. Intersecting with disability, patriarchy, sexism and misogyny mark disabled womenâs lives in particular ways. For example, through our forced sterilization (taking away our ability to give birth); through our higher rates of sexual and intimate partner violence; through the broad denial of our sexual selves; through the chastising and punishing of our sexual desires within institutional spaces (like group homes) (particularly LGBTQQI2-S disabled people); through inhibiting our rights to love and be loved; through denying our rightful access to sexual support, information and education; through barriers within sexual and reproductive healthcare; and through the typical shaming of our sexual bodies, desires, and pleasures.

In this article, I write as both a disabled woman and a researcher. I discuss the sexual and intimate stories told by disabled women through my doctoral research which sought to explore the relationships between disability, sex, intimacy, and love. Crucially, I bring forward the voices of these women, applying their own words to embody the issues discussed. I do this not only because, politically, itâs important that my voice isnât the only one (re)telling peopleâs stories, but because it offers the opportunity to identify, or relate to, the stories and words of others â regardless of disability status. Far from being âdegenderedâ or stripped of gender, as disabled women often are in our culture, disabled women in my research told their stories first and foremost as women. While the women in my research identified as cis-women, I use the words âwomanâ and âwomenâ in this article with a broad, inclusive and diverse understanding of âwomanhoodâ; one which is inclusive of all cis, trans, and gender-queer women. While this is my personal anti-oppressive definition of woman and women, this study does not provide a trans-inclusive analysis of experiences with sex and disability, since participants identified as cis-gendered women. Therefore, my aim here is to (re)tell these intricate and intimate stories, drawing attention to the pleasures, fears, loves and uncertainties most prominent within disabled womenâs stories about their own lives.

Secret Loves, Hidden Lives While the individual stories of both disabled men and women were marked in different ways by gender, race, class, nationality, age, religion, impairment type (e.g. sensory/physical) and the origins of impairment (whether acquired or congenital/from birth), disabled womenâs collective sexual story was distinctly molded by heteronormativity, heterosexuality, and patriarchy. While heterosexuality is a sexual orientation, heteronormativity is the idea that heterosexuality â as a sexual preference, lifestyle, and societal institution â is the set norm from which all other sexual orientations and identities deviate. Noticeably, most women in the research tended to speak through a veil of (sexual) shame, embarrassed to articulate their pleasures and desires. It also wasnât uncommon for whole chapters of womenâs stories to be dedicated to their self-hatred and lack of body and sexual confidence, and there was an identifiable collective feeling of not embodying ableist and sexist ideals of womanhood âproperlyâ or âappropriatelyâ enough, for both themselves and their partners.

Sally(4): âWho would want to have sex with me when there are plenty of normal girls more than willing?â

Lucille: âI felt so bad about not wanting sex [after injury] that I kept telling him to have an affairâ.

Jenny: [After a date] âHis father came out to my car and told me to fuck off. He [boyfriend] didnât have any disability⊠He said âfuck off you cripple and leave my son aloneââ.

This lack of confidence was further emphasised through womenâs descriptions of their roles within their sexual and intimate relationships with others, and their own experiences of sexual pleasure and desire. While both men and women expressed great frustration at typically ableist (hetero)sexual norms â norms which dictate a fully-functioning, autonomous, mobile, âsexyâ, strong and supple body for physical, penetrative, goal-orientated and genitally-focused activity â disabled men, for the most part, could negotiate a more empowering sexual role within their sexual lives and build a positive sexual identity.

For example, most men could often successfully negotiate dis/ableism(5), bodily impairment and constructions of masculinity (many of which are deeply oppressive for disabled men) to claim a gendered sexual self with which they were happy; one underpinned by body confidence and self-love, and through which they could experience sexual pleasure and desire without shame. Disabled menâs greater social and sexual power (afforded to them through patriarchy) also ensured greater practical sexual support from attendants, carers, and parents, which enabled better access to sex and sexuality than disabled women. In contrast, the majority of disabled women didnât have the esteem or confidence to negotiate a desired role in sex; nor could they find a route to body confidence and self-love. Many women reported receiving little support within their sexual lives, saying that their desires were often overlooked by the people who provided their care. Most felt unfulfilled, inadequate and frustrated. All of these issues are compounded for LGBTQQI2-S disabled people (particularly disabled Trans people) whose identities often remain unrecognizable and Othered in the context of care and caring.

Rhona: âAlthough I knew that he adored me, I also always felt slightly as though I didnât deserve him. I am a logical person, and I know that disability puts you further down the relationship league table.â

Jane: âI am unhappy [in the relationship] a lot. But Iâm scared no one else would accept me. I just think people donât accept people who are different.â

For some, a lack of self-love was compounded by experiences of violence. Disabled women experience higher rates of sexual violence than both disabled men and non-disabled (âable-bodiedâ) women (Canadian Womenâs Foundation, 2011). These experiences of violence are heightened by the lack of privacy which is endemic to the disabled experience, but also by the fact that there is very little service provision for disabled women to report or escape sexual, physical and emotional violence. For disabled women of colour, aboriginal women, immigrant and refugee women and Trans women this can be further exacerbated by racism, ethnocentrism, xenophobia and transphobia. Therefore, a lack of violence support services which are accessible, culturally-appropriate and knowledgeable about LGBTQQI2-S issues adds to the problem.

Grace : âHe wanted (and got) sex at least twice a day every day. Sometimes we had sex more than twice a day â even up to five times a day. It didnât matter if I had my period or if I felt unwell or was pregnant. He wanted sex. If I refused, he made my life a misery, sulking and getting angry and taunting me. It was easier to do as he wanted. I seldom ever enjoyed it. And there was my deafness. I had left school with no qualifications, no career [her education was inaccessible]. A dead end job and an early marriage and children meant I had hardly any skills outside the home. He isolated me from my friends. He could not cope with me being deaf; as my deafness increased, he found it harder. He did not want a deaf wife. He hit me a few times.â

For other women, the difficulty in claiming positive sexual selfhood was further ground in the loud silences which surround the (sexual) lives of heterosexual and LGBTQQI2-S disabled women in mainstream culture. Representations of our sexual lives, selves and bodies seldom feature anywhere within popular culture. Where they do â for example, in films and on television â we are usually depicted as sexless, burdensome and pitiful. Interestingly, disabled peopleâs own (rights) movements have historically echoed this silence; it is only relatively recently that sex and sexuality â disabled peopleâs sexual politics â have been loudly and proudly placed on disability rights and justice agendas.

Gemma: âAnd, he [doctor] was just totally embarrassed. I thought âhow bizarreâ, he just didnât want to tackle it at all. He was totallyâŠaghastâŠdidnât comment and carried on [laughs]⊠I think having a couple of lesbians discussing their orgasms was not what he had in mind [âŠ] I just think thatâs quite telling, really.â

Helen: âWhen I was younger I remember this one guy at school said âCan you have sex?â I was like âYeah!â⊠Getting people to see past the chair⊠itâs difficult.â

Cripping Sex: What is a sexy body? While many seldom recognised it â or had the resources to claim it â the stories of some women explicitly showed the sheer and utter sexiness of difference and disability. Bodies which are both classified and labeled as impaired, ânon-normativeâ, or different can truly challenge societyâs prescriptive ideas of what constitutes a sexy body. These unique bodies can also radically crip(6) â or disrupt â sexual norms, opening up new possibilities and potentialities for pleasure. For example, some people spoke of experiencing many different types of pleasure outside of the quantified, measured, and charted key stages within the human sexual experience of arousal, climax and orgasm â aspects of sexuality which are aggressively positioned as necessary, even compulsory, within sex. I quickly realised that our cripped and queered bodies can subvert and expand sex in spaces where, for non-impaired (âableâ) bodies, the scope for transformation may be limited.

Rhona: âSex was brilliant, and we both enjoyed each other immensely: Intimacy, proximity, sensations, comedy, lack of control, feeling desired, being treated roughly and not as though I might break. It is also one of the few examples of when my body allows me a âtime-outâ, and I feel liberated. Done right, it is all pleasure and no pain.â

To go a little further, it is our beautifully complex bodies and minds which offer a glimmer of how conventional bodily pleasures, only ever physical and bodily, can be cripped and queered, in order to expand âsexâ to include our minds, senses, imagination and spirituality. For example, the imagination was a central form of eroticism for many of those who took part in the research. Many women said that their imagined erotic experiences were the times when they felt the sexiest and most turned on. Others, who had displaced erogenous zones (which can result from spinal injury), could orgasm through stroking arms or feet. For example, one disabled man who had found it difficult to orgasm in the conventional way discovered that he could orgasm through his partner stroking his shoulders. This inevitably led to many nights of shoulder stroking⊠and shows how disabled bodies can expand and envelope pleasure in new, exciting ways.

Hannah: âSo that was an eye opener, that wow, an orgasm through touching above the injury⊠itâs amazing reallyâŠâ

Others de-centred the orgasm or traditional gendered roles within their intimate practices all together, usually on the grounds that these rigid sexual norms just didnât fit their embodiment (their experiences of their bodies). One couple decentered the orgasm because, they said, relentlessly âchasingâ it was becoming overwhelming. As such, they found that their closeness, intimacy and affection grew immeasurably once they had learned how to have a great sex life together without orgasm. Others explored how the spasticity of muscles (which can occur within any number of conditions, such as Cerebral Palsy and Spina Bifida) could enhance and their orgasms and enrich their experiences of pleasure.

Lucille: âI canât feel any sensation that one would normally have but the way I feel does change in a way I canât describe. Teamed with my imagination it can be very pleasant, makes me feel sexy.â

Others got great pleasure from being treated roughly, as a departure from the ways in which their bodies were (routinely) treated as though they were inherently breakable or fragile. Further, while many found that disability could mean a lack of spontaneity in sex (spontaneity, I add, which is depicted in every Hollywood sex scene âcos, apparently, sex needs zero discussion), they also said that planning made sex more enjoyable, and that it enabled the development of more elaborate and imaginative sex play.

For some, the presence of disability and bodily difference were a means to reject what disability scholar Tom Shakespeare (2000: 164) calls the âCosmo conspiracy of great sexâ. This is the (false) idea that all people are having incredible sex, all of the time â which just isnât true. The sexual stories collected in my research showed that enjoyable sex isnât natural, but takes work: open discussion with partners; understanding a partnerâs likes and dislikes; lots of experimentation with sex and pleasure; and lots of work on the intimacy which can precede sex. While disability was the impetus for many of these intimate labours, these alternative sexual ways of being suggest that there is much to learn from disability when it comes to sex and intimacy.

To sum up a little, these experiences emphasize how crucial it is for disabled women â and all women and girls â to reclaim âsexyâ from the deeply oppressive ways in which it is proliferated and maintained in our cultures: a mode of sexuality that is considered ânaturalâ but is, in reality, anything but, being routinely learned and relearned; taught, policed, and regulated throughout our lives.

Conclusions⊠I finish by asking, then, how can all of us strive to become shameless in our sexual lives? How can we rid ourselves of the shame that is often endemic to our experiences, lives and bodies, regardless of whether we â as women â live with disability, or not? The storied lives of disabled women in my research have shown this can only happen by sharing our stories, lives and experiences. Stories can â if voiced and heard â be productive, useful, and valuable. Stories can define a place and people. They offer a sense of collective experience; a means to claim space, foster a positive identities and experiences, and demand social and sexual justice. Collectively, telling and sharing our stories is how we can build sexual cultures and communities as we want them; ones which fit all of our bodies, pleasures and desires; ones which empower rather than oppress. So, whatâs your sexual story?

Kirsty Liddiard PhD. is currently the Ethel Louise Armstrong Postdoctoral Fellow within the School of Disability Studies, Ryerson University, where she lectures and teaches on a range of disability issues. Kirsty considers herself a proud disabled woman and activist, critical disability theorist, and feminist. You can read her at kirsty.liddiard@ryerson.ca.

- This article uses the terms âdisabled peopleâ and âdisabled personâ rather than âpeople firstâ terminology (âpeople with disabilitiesâ or âperson with a disabilityâ). This reflects the position that disability, while part of identity, is not intrinsically embodied within the person, and is not individual or medical. Instead, disability is the sum of systemic, attitudinal, environmental, political, economic and cultural barriers within society.

- The asexual identity ascribed to disabled people is situated outside of the proud asexual identity chosen by the asexual community.

- LGBTQQI2-S: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning, Queer, Intersex and 2-Spirit (LGBTQQI2-S) communities.

- All names have been changed.

- The term âdis/ableismâ refers to the dual processes of disablism and ableism. Disablism is a form of direct discrimination or prejudice on the grounds of disability; ableism is a broader network of cultural beliefs whereby the non-disabled/âableâ body and mind are the norm against which the value of all other bodies and minds are determined.

- The term crip has been reclaimed by many disabled people from the derogatory term âcrippleâ. Through Crip theory and Crip politics, the meaning of crip has become synonymous with resistance, pride, and non-normativity as a means of strength. I use crip as a verb, to refer to the process by which disability can fundamentally undermine the oppressive ideology of the norm, as well as to expose how âable-bodiednessâ is naturalized (considered natural) and established.

References

âą Canadian Womenâs Foundation (2011) The Facts About Violence Against Women. Online. [Accessed 09.11.2013]. Available online here.

âą Shakespeare, T. (2000) âDisabled Sexuality: Toward Rights and Recognitionâ, Sexuality and Disability, 18: 3, 159-166